Chronology of the universe

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2023) |

| Part of a series on |

| Physical cosmology |

|---|

|

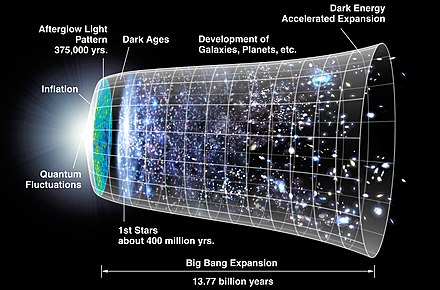

The chronology of the universe describes the history and future of the universe according to Big Bang cosmology.

Research published in 2015 estimates the earliest stages of the universe's existence as taking place 13.8 billion years ago, with an uncertainty of around 21 million years at the 68% confidence level.[1]

−13 — – −12 — – −11 — – −10 — – −9 — – −8 — – −7 — – −6 — – −5 — – −4 — – −3 — – −2 — – −1 — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overview

[edit]Chronology in five stages

[edit]

For the purposes of this summary, it is convenient to divide the chronology of the universe since it originated, into five parts. It is generally considered meaningless or unclear whether time existed before this chronology:

The very early universe

[edit]The first picosecond (10−12 seconds) of cosmic time includes the Planck epoch,[2] during which currently established laws of physics may not have applied; the emergence in stages of the four known fundamental interactions or forces—first gravitation, and later the electromagnetic, weak and strong interactions; and the accelerated expansion of the universe due to cosmic inflation.

Tiny ripples in the universe at this stage are believed to be the basis of large-scale structures that formed much later. Different stages of the very early universe are understood to different extents. The earlier parts are beyond the grasp of practical experiments in particle physics but can be explored through the extrapolation of known physical laws to extremely high temperatures.

The early universe

[edit]This period lasted around 380,000 years. Initially, various kinds of subatomic particles are formed in stages. These particles include almost equal amounts of matter and antimatter, so most of it quickly annihilates, leaving a small excess of matter in the universe.

At about one second, neutrinos decouple; these neutrinos form the cosmic neutrino background (CνB). If primordial black holes exist, they are also formed at about one second of cosmic time. Composite subatomic particles emerge—including protons and neutrons—and from about 2 minutes, conditions are suitable for nucleosynthesis: around 25% of the protons and all the neutrons fuse into heavier elements, initially deuterium which itself quickly fuses into mainly helium-4.

By 20 minutes, the universe is no longer hot enough for nuclear fusion, but far too hot for neutral atoms to exist or photons to travel far. It is therefore an opaque plasma.

The recombination epoch begins at around 18,000 years, as electrons are combining with helium nuclei to form He+

. At around 47,000 years,[3] as the universe cools, its behavior begins to be dominated by matter rather than radiation. At around 100,000 years, after the neutral helium atoms form, helium hydride is the first molecule. Much later, hydrogen and helium hydride react to form molecular hydrogen (H2) the fuel needed for the first stars. At about 370,000 years,[4][5][6][7] neutral hydrogen atoms finish forming ("recombination"), and as a result the universe also became transparent for the first time. The newly formed atoms—mainly hydrogen and helium with traces of lithium—quickly reach their lowest energy state (ground state) by releasing photons ("photon decoupling"), and these photons can still be detected today as the cosmic microwave background (CMB). This is the oldest direct observation we currently have of the universe.

The Dark Ages and large-scale structure emergence

[edit]

This period measures from 380,000 years until about 1 billion years. After recombination and decoupling, the universe was transparent but the clouds of hydrogen only collapsed very slowly to form stars and galaxies, so there were few sources of light and the emission from these sources was immediately absorbed by hydrogen atoms. The only photons (electromagnetic radiation, or "light") in the universe were those released during decoupling (visible today as the cosmic microwave background) and 21 cm radio emissions occasionally emitted by hydrogen atoms. This period is known as the cosmic Dark Ages.[citation needed]

At some point around 200 to 500 million years, the earliest generations of stars and galaxies form (exact timings are still being researched), and early large structures gradually emerge, drawn to the foam-like dark matter filaments which have already begun to draw together throughout the universe. The earliest generations of stars have not yet been observed astronomically. They may have been very massive (100–300 solar masses) and non-metallic, with very short lifetimes compared to most stars we see today, so they commonly finish burning their hydrogen fuel and explode as highly energetic pair-instability supernovae after mere millions of years.[9] Other theories suggest that they may have included small stars, some perhaps still burning today. In either case, these early generations of supernovae created most of the every day elements we see around us today, and seeded the universe with them.

Galaxy clusters and superclusters emerge over time. At some point, high-energy photons from the earliest stars, dwarf galaxies and perhaps quasars lead to a period of reionization that commences gradually between about 250–500 million years and finishes by about 1 billion years (exact timings still being researched). The Dark Ages only fully came to an end at about 1 billion years as the universe gradually transitioned into the universe we see around us today, but denser, hotter, more intense in star formation, and richer in smaller (particularly unbarred) spiral and irregular galaxies, as opposed to giant elliptical galaxies.

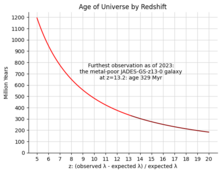

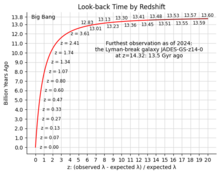

While early stars have not been observed, galaxies have been observed from 329 million years since the Big Bang, with JADES-GS-z13-0 which the James Webb Space Telescope observed with a redshift of z=13.2, from 13.4 billion years ago.[10][11] The JWST was designed to observe as far as z≈20 (180 million years cosmic time).[citation needed]

The universe as it appears today

[edit]From 1 billion years, and for about 12.8 billion years, the universe has looked much as it does today and it will continue to appear very similar for many billions of years into the future. The thin disk of our galaxy began to form at about 5 billion years (8.8 Gya),[12] and the Solar System formed at about 9.2 billion years (4.6 Gya), with the earliest evidence of life on Earth emerging by about 10 billion years (3.8 Gya).

The thinning of matter over time reduces the ability of gravity to decelerate the expansion of the universe; in contrast, dark energy (believed to be a constant scalar field throughout the visible universe) is a constant factor tending to accelerate the expansion of the universe. The universe's expansion passed an inflection point about five or six billion years ago when the universe entered the modern "dark-energy-dominated era" where the universe's expansion is now accelerating rather than decelerating. The present-day universe is quite well understood, but beyond about 100 billion years of cosmic time (about 86 billion years in the future), we are less sure which path the universe will take.[13][14]

The far future and ultimate fate

[edit]At some time, the Stelliferous Era will end as stars are no longer being born, and the expansion of the universe will mean that the observable universe becomes limited to local galaxies. There are various scenarios for the far future and ultimate fate of the universe. More exact knowledge of the present-day universe may allow these to be better understood.

Tabular summary

[edit]- Note: The radiation temperature in the table below refers to the cosmic microwave background radiation and is given by 2.725 K·(1 + z), where z is the redshift.

| Epoch | Time | Redshift | Radiation temperature (Energy) [verification needed] |

Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planck epoch | < 10−43 s | > 1032 K ( > 1019 GeV) |

The Planck scale is the physical scale beyond which current physical theories may not apply and cannot be used to reliably predict any events. During the Planck epoch, cosmology and physics are assumed to have been dominated by the quantum effects of gravity. | |

| Grand unification epoch | < 10−36 s | > 1029 K ( > 1016 GeV) |

The three forces of the Standard Model are still unified (assuming that nature is described by a Grand Unified Theory, gravity not included). | |

| Inflationary epoch Electroweak epoch |

< 10−32 s | 1028 K ~ 1022 K (1015 ~ 109 GeV) |

Cosmic inflation expands space by a factor of the order of 1026 over a time of the order of 10−36 to 10−32 seconds. The universe is supercooled from about 1027 down to 1022 Kelvins.[15] The strong interaction becomes distinct from the electroweak interaction. | |

| Electroweak epoch ends | 10−12 s | 1015 K (150 GeV) |

Before temperature falls below 150 GeV, the average energy of particle interactions is high enough that it is more succinct to describe them as an exchange of W1, W2, W3, and B vector bosons (electroweak interactions) and H+, H−, H0, H0⁎ scalar bosons (Higgs interaction). In this picture, the vacuum expectation value of the Higgs field is zero (therefore, all fermions are massless), all electroweak bosons are massless (they had not yet subsumed a component of the Higgs field to become massive), and photons (γ) do not yet exist (they will exist after a phase transition as a linear combination of B and W3 bosons, γ = B cos θW + W3 sin θW, where θW is the Weinberg angle). These are the highest energies directly observable in the Large Hadron Collider. The sphere of space that will become the observable universe is approximately 300 light-seconds (~0.6 AU) in radius at this time. | |

| Quark epoch | 10−12 s ~ 10−5 s | 1015 K ~ 1012 K (150 GeV ~ 150 MeV) |

The forces of the Standard Model have reorganized into the "low-temperature" form: Higgs and electroweak interactions rearranged into massive Higgs boson H0, weak force carried by massive W+, W–, and Z0 bosons, and electromagnetism carried by massless photons. Higgs field has a nonzero vacuum expectation value, making fermions massive. Energies are too high for quarks to coalesce into hadrons, instead forming a quark–gluon plasma. | |

| Hadron epoch | 10−5 s ~ 1 s | 1012 K ~ 1010 K (150 MeV ~ 1 MeV) |

Quarks are bound into hadrons. A slight matter-antimatter asymmetry from the earlier phases (baryon asymmetry) results in an elimination of anti-baryons. Until 0.1 s, muons and pions are in thermal equilibrium, and outnumber baryons by about 10:1. Close to the end of this epoch, only light-stable baryons (protons and neutrons) remain. Due to the sufficiently high density of leptons, protons and neutrons rapidly change into one another under the action of weak force. Due to the higher mass of neutron the neutron:proton ratio, which is initially 1:1, starts to decrease. | |

| Neutrino decoupling | 1 s | 1010 K (1 MeV) |

Neutrinos cease interacting with baryonic matter, and form cosmic neutrino background. Neutron:proton ratio freezes at approximately 1:6. The sphere of space that will become the observable universe is approximately 10 light-years in radius at this time. | |

| Lepton epoch | 1 s ~ 10 s | 1010 K ~ 109 K (1 MeV ~ 100 keV) |

Leptons and antileptons remain in thermal equilibrium—energy of photons is still high enough to produce electron-positron pairs. | |

| Big Bang nucleosynthesis | 10 s ~ 103 s | 109 K ~ 107 K (100 keV ~ 1 keV) |

Protons and neutrons are bound into primordial atomic nuclei: hydrogen and helium-4. Trace amounts of deuterium, helium-3, and lithium-7 also form. At the end of this epoch, the spherical volume of space which will become the observable universe is about 300 light-years in radius, baryonic matter density is on the order of 4 grams per m3 (about 0.3% of sea level air density)—however, most energy at this time is in electromagnetic radiation. | |

| Photon epoch | 10 s ~ 370 ka | 109 K ~ 4000 K (100 keV ~ 0.4 eV) |

The universe consists of a plasma of nuclei, electrons, and photons; temperature is too low to create electron-positron pairs (or any other pairs of massive particles), but too high for the binding of electrons to nuclei. | |

| Recombination | 18 ka ~ 370 ka | 6000 ~ 1100 | 4000 K (0.4 eV) |

Electrons and atomic nuclei first become bound to form neutral atoms. Photons are no longer in thermal equilibrium with matter and the universe first becomes transparent. Recombination lasts for about 100 ka, during which the universe is becoming more and more transparent to photons. The photons of the cosmic microwave background radiation originate at this time. The spherical volume of space that will become the observable universe is 42 million light-years in radius at this time. The baryonic matter density at this time is about 500 million hydrogen and helium atoms per m3, approximately a billion times higher than today. This density corresponds to pressure on the order of 10−17 atm. |

| Dark Ages | 370 ka ~ 150 Ma? (Only fully ends by about 1 Ga) |

1100 ~ 20 | 4000 K ~ 60 K | The time between recombination and the formation of the first stars. During this time, the only source of photons was hydrogen emitting radio waves at hydrogen line. Freely propagating CMB photons quickly (within about 3 million years) red-shifted to infrared, and the universe was devoid of visible light. |

| Star and galaxy formation and evolution | Earliest galaxies: from about 300–400 Ma? (first stars: similar or earlier) Modern galaxies: 1 Ga ~ 10 Ga (Exact timings being researched) |

From about 20 | From about 60 K | The earliest known galaxies existed by about 380 Ma. Galaxies coalesce into "proto-clusters" from about 1 Ga (redshift z = 6 ) and into galaxy clusters beginning at 3 Ga ( z = 2.1 ), and into superclusters from about 5 Ga ( z = 1.2 ). See: list of galaxy groups and clusters, list of superclusters. |

| Reionization | 200 Ma ~ 1 Ga (Exact timings being researched) |

20 ~ 6 | 60 K ~ 19 K | The most distant astronomical objects observable with telescopes date to this period; as of 2016[update], the most remote galaxy observed is GN-z11, at a redshift of 11.09. The earliest "modern" Population I stars are formed in this period. |

| Present time | 13.8 Ga | 0 | 2.7 K | Farthest observable photons at this moment are CMB photons. They arrive from a sphere with a radius of 46 billion light-years. The spherical volume inside it is commonly referred to as the observable universe. |

| Alternative subdivisions of the chronology (overlapping several of the above periods) | ||||

| Radiation-dominated era | From inflation (~ 10−32 sec) ~ 47 ka | > 3600 | > 104 K | During this time, the energy density of massless and near-massless relativistic components such as photons and neutrinos, which move at or close to the speed of light, dominate both matter density and dark energy. |

| Matter-dominated era | 47 ka ~ 9.8 Ga[3] | 3600 ~ 0.4 | 104 K ~ 4 K | During this time, the energy density of matter dominates both radiation density and dark energy, resulting in a decelerated expansion of the universe. |

| Dark energy dominated era | > 9.8 Ga[13] | < 0.4 | < 4 K | Matter density falls below dark energy density (vacuum energy), and expansion of space begins to accelerate. This time happens to correspond roughly to the time of the formation of the Solar System and the evolutionary history of life. |

| Stelliferous Era | 150 Ma ~ 100 Ta[16] | 20 ~ −0.99 | 60 K ~ 0.03 K | The time between the first formation of Population III stars until the cessation of star formation, leaving all stars in the form of degenerate remnants. |

| Far future | > 100 Ta[16] | < −0.99 | < 0.1 K | The Stelliferous Era will end as stars eventually die and fewer are born to replace them, leading to a darkening universe. Various theories suggest a number of subsequent possibilities. Assuming proton decay, the matter may eventually evaporate into a Dark Era (heat death). Alternatively, the universe may collapse in a Big Crunch. Other suggested ends include a false vacuum catastrophe or a Big Rip as possible ends to the universe. |

The Big Bang

[edit]The Standard Model of cosmology is based on a model of spacetime called the Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker (FLRW) metric. A metric provides a measure of distance between objects, and the FLRW metric is the exact solution of Einstein field equations (EFE) if some key properties of space such as homogeneity and isotropy are assumed to be true. The FLRW metric very closely matches overwhelming other evidence, showing that the universe has expanded since the Big Bang.

If the FLRW metric equations are assumed to be valid all the way back to the beginning of the universe, they can be followed back in time, to a point where the equations suggest all distances between objects in the universe were zero or infinitesimally small. (This does not necessarily mean that the universe was physically small at the Big Bang, although that is one of the possibilities.) This provides a model of the universe which matches all current physical observations extremely closely. This initial period of the universe's chronology is called the "Big Bang". The Standard Model of cosmology attempts to explain how the universe physically developed once that moment happened.

The singularity from the FLRW metric is interpreted to mean that current theories are inadequate to describe what actually happened at the start of the Big Bang itself. It is widely believed that a correct theory of quantum gravity may allow a more correct description of that event, but no such theory has yet been developed. After that moment, all distances throughout the universe began to increase from (perhaps) zero because the FLRW metric itself changed over time, affecting distances between all non-bound objects everywhere. For this reason, it is said that the Big Bang "happened everywhere".

The very early universe

[edit]Planck epoch

[edit]- Times shorter than 10−43 seconds (Planck time)

The Planck epoch is an era in traditional (non-inflationary) Big Bang cosmology immediately after the event that began the known universe. During this epoch, the temperature and average energies within the universe were so high that subatomic particles could not form. The four fundamental forces that shape the universe—gravitation, electromagnetism, the weak nuclear force, and the strong nuclear force—comprised a single fundamental force. Little is understood about physics in this environment. Traditional big bang cosmology predicts a gravitational singularity—a condition in which spacetime breaks down—before this time, but the theory relies on the theory of general relativity, which is thought to break down for this epoch due to quantum effects.[17]

In inflationary models of cosmology, times before the end of inflation (roughly 10−32 seconds after the Big Bang) do not follow the same timeline as in traditional Big Bang cosmology. Models that aim to describe the universe and physics during the Planck epoch are generally speculative and fall under the umbrella of "New Physics". Examples include the Hartle–Hawking initial state, string theory landscape, string gas cosmology, and the ekpyrotic universe.

Grand unification epoch

[edit]- Between 10−43 seconds and 10−36 seconds after the Big Bang[18]

As the universe expanded and cooled, it crossed transition temperatures at which forces separated from each other. These cosmological phase transitions can be visualized as similar to condensation and freezing phase transitions of ordinary matter. At certain temperatures/energies, water molecules change their behavior and structure, and they will behave completely differently. Like steam turning to water, the fields which define the universe's fundamental forces and particles also completely change their behaviors and structures when the temperature/energy falls below a certain point. This is not apparent in everyday life, because it only happens at far higher temperatures than usually seen in the present-day universe.

These phase transitions in the universe's fundamental forces are believed to be caused by a phenomenon of quantum fields called "symmetry breaking".

In everyday terms, as the universe cools, it becomes possible for the quantum fields that create the forces and particles around us, to settle at lower energy levels and with higher levels of stability. In doing so, they completely shift how they interact. Forces and interactions arise due to these fields, so the universe can behave very differently above and below a phase transition. For example, in a later epoch, a side effect of one phase transition is that suddenly, many particles that had no mass at all acquire a mass (they begin to interact differently with the Higgs field), and a single force begins to manifest as two separate forces.

Assuming that nature is described by a so-called Grand Unified Theory (GUT), the grand unification epoch began with a phase transition of this kind, when gravitation separated from the universal combined gauge force. This caused two forces to now exist: gravity, and an electrostrong interaction. There is no hard evidence yet that such a combined force existed, but many physicists believe it did. The physics of this electrostrong interaction would be described by a Grand Unified Theory.

The grand unification epoch ended with a second phase transition, as the electrostrong interaction in turn separated, and began to manifest as two separate interactions, called the strong and the electroweak interactions.

Electroweak epoch

[edit]- Between 10−36 seconds (or the end of inflation) and 10−32 seconds after the Big Bang[18]

Depending on how epochs are defined, and the model being followed, the electroweak epoch may be considered to start before or after the inflationary epoch. In some models, it is described as including the inflationary epoch. In other models, the electroweak epoch is said to begin after the inflationary epoch ended, at roughly 10−32 seconds.

According to traditional Big Bang cosmology, the electroweak epoch began 10−36 seconds after the Big Bang, when the temperature of the universe was low enough (1028 K) for the electronuclear force to begin to manifest as two separate interactions, the strong and the electroweak interactions. (The electroweak interaction will also separate later, dividing into the electromagnetic and weak interactions.) The exact point where electrostrong symmetry was broken is not certain, owing to speculative and as yet incomplete theoretical knowledge.

Inflationary epoch and the rapid expansion of space

[edit]- Before c. 10−32 seconds after the Big Bang

At this point of the very early universe, the universe is thought to have expanded by a factor of at least 1078 in volume. This is equivalent to a linear increase of at least 1026 times in every spatial dimension—equivalent to an object 1 nanometre (10−9 m, about half the width of a molecule of DNA) in length, expanding to one approximately 10.6 light-years (100 trillion kilometres) long in a tiny fraction of a second. This phase of the cosmic expansion history is known as inflation.

The mechanism that drove inflation remains unknown, although many models have been put forward. In several of the more prominent models, it is thought to have been triggered by the separation of the strong and electroweak interactions which ended the grand unification epoch. One of the theoretical products of this phase transition was a scalar field called the inflaton field.[19] As this field settled into its lowest energy state throughout the universe, it generated an enormous repulsive force that led to a rapid expansion of the universe. Inflation explains several observed properties of the current universe that are otherwise difficult to account for, including explaining how today's universe has ended up so exceedingly homogeneous (spatially uniform) on a very large scale, even though it was highly disordered in its earliest stages.

It is not known exactly when the inflationary epoch ended, but it is thought to have been between 10−33 and 10−32 seconds after the Big Bang. The rapid expansion of space meant that elementary particles remaining from the grand unification epoch were now distributed very thinly across the universe. However, the huge potential energy of the inflaton field was released at the end of the inflationary epoch, as the inflaton field decayed into other particles, known as "reheating". This heating effect led to the universe being repopulated with a dense, hot mixture of quarks, anti-quarks and gluons. In other models, reheating is often considered to mark the start of the electroweak epoch, and some theories, such as warm inflation, avoid a reheating phase entirely.

In non-traditional versions of Big Bang theory (known as "inflationary" models), inflation ended at a temperature corresponding to roughly 10−32 seconds after the Big Bang, but this does not imply that the inflationary era lasted less than 10−32 seconds. To explain the observed homogeneity of the universe, the duration in these models must be longer than 10−32 seconds. Therefore, in inflationary cosmology, the earliest meaningful time "after the Big Bang" is the time of the end of inflation.

After inflation ended, the universe continued to expand, but at a decelerating rate. About 4 billion years ago the expansion gradually began to speed up again. This is believed to be due to dark energy becoming dominant in the universe's large-scale behavior. It is still expanding (and accelerating), today.

On 17 March 2014, astrophysicists of the BICEP2 collaboration announced the detection of inflationary gravitational waves in the B-modes power spectrum which was interpreted as clear experimental evidence for the theory of inflation.[20][21][22][23][24] However, on 19 June 2014, lowered confidence in confirming the cosmic inflation findings was reported [23][25][26] and finally, on 2 February 2015, a joint analysis of data from BICEP2/Keck and the European Space Agency's Planck microwave space telescope concluded that the statistical "significance [of the data] is too low to be interpreted as a detection of primordial B-modes" and can be attributed mainly to polarized dust in the Milky Way.[27][28][29]

Supersymmetry breaking (speculative)

[edit]If supersymmetry is a property of the universe, then it must be broken at an energy that is no lower than 1 TeV, the electroweak scale. The masses of particles and their superpartners would then no longer be equal. This very high energy could explain why no superpartners of known particles have ever been observed.

The early universe

[edit]After cosmic inflation ends, the universe is filled with a hot quark–gluon plasma, the remains of reheating. From this point onwards the physics of the early universe is much better understood, and the energies involved in the Quark epoch are directly accessible in particle physics experiments and other detectors.

Electroweak epoch and early thermalization

[edit]- Starting anywhere between 10−22 and 10−15 seconds after the Big Bang, until 10−12 seconds after the Big Bang

Sometime after inflation, the created particles went through thermalization, where mutual interactions lead to thermal equilibrium. Before the electroweak symmetry breaking, at a temperature of around 1015 K, approximately 10−15 seconds after the Big Bang, the electromagnetic and weak interaction have not yet separated, and the gauge bosons and fermions have not yet gained mass through the Higgs mechanism. This epoch ended with electroweak symmetry breaking, potentially through a phase transition. In some extensions of the Standard Model of particle physics, baryogenesis also happened at this stage, creating an imbalance between matter and anti-matter (though in extensions to this model, this may have happened earlier). Little is known about the details of these processes.

Thermalization

[edit]The number density of each particle species was, by a similar analysis to Stefan–Boltzmann law:

- ,

which is roughly just . Since the interaction was strong, the cross-section was approximately the particle wavelength squared, which is roughly . The rate of collisions per particle species can thus be calculated from the mean free path, giving approximately:

- .

For comparison, since the cosmological constant was negligible at this stage, the Hubble parameter was:

- ,

where x ~ 102 was the number of available particle species.[notes 1]

Thus H is orders of magnitude lower than the rate of collisions per particle species. This means there was plenty of time for thermalization at this stage.

At this epoch, the collision rate is proportional to the third root of the number density, and thus to , where is the scale parameter. The Hubble parameter, however, is proportional to . Going back in time and higher in energy, and assuming no new physics at these energies, a careful estimate gives that thermalization was first possible when the temperature was:[30]

- ,

approximately 10−22 seconds after the Big Bang.

Electroweak symmetry breaking

[edit]- 10−12 seconds after the Big Bang

As the universe's temperature continued to fall below 159.5±1.5 GeV, electroweak symmetry breaking happened.[31] So far as we know, it was the penultimate symmetry breaking event in the formation of the universe, the final one being chiral symmetry breaking in the quark sector. This has two related effects:

- Via the Higgs mechanism, all elementary particles interacting with the Higgs field become massive, having been massless at higher energy levels.

- As a side-effect, the weak nuclear force and electromagnetic force, and their respective bosons (the W and Z bosons and photon) now begin to manifest differently in the present universe. Before electroweak symmetry breaking these bosons were all massless particles and interacted over long distances, but at this point the W and Z bosons abruptly become massive particles only interacting over distances smaller than the size of an atom, while the photon remains massless and remains a long-distance interaction.

After electroweak symmetry breaking, the fundamental interactions we know of—gravitation, electromagnetic, weak and strong interactions—have all taken their present forms, and fundamental particles have their expected masses, but the temperature of the universe is still too high to allow the stable formation of many particles we now see in the universe, so there are no protons or neutrons, and therefore no atoms, atomic nuclei, or molecules. (More exactly, any composite particles that form by chance, almost immediately break up again due to the extreme energies.)

The quark epoch

[edit]- Between 10−12 seconds and 10−5 seconds after the Big Bang

The quark epoch began approximately 10−12 seconds after the Big Bang. This was the period in the evolution of the early universe immediately after electroweak symmetry breaking when the fundamental interactions of gravitation, electromagnetism, the strong interaction and the weak interaction had taken their present forms, but the temperature of the universe was still too high to allow quarks to bind together to form hadrons.[32][33][better source needed]

During the quark epoch the universe was filled with a dense, hot quark–gluon plasma, containing quarks, leptons and their antiparticles. Collisions between particles were too energetic to allow quarks to combine into mesons or baryons.[32]

The quark epoch ended when the universe was about 10−5 seconds old, when the average energy of particle interactions had fallen below the mass of the lightest hadron, the pion.[32]

Baryogenesis

[edit]- Perhaps by 10−11 seconds[citation needed]

Baryons are subatomic particles such as protons and neutrons, that are composed of three quarks. It would be expected that both baryons, and particles known as antibaryons would have formed in equal numbers. However, this does not seem to be what happened—as far as we know, the universe was left with far more baryons than antibaryons. In fact, almost no antibaryons are observed in nature. It is not clear how this came about. Any explanation for this phenomenon must allow the Sakharov conditions related to baryogenesis to have been satisfied at some time after the end of cosmological inflation. Current particle physics suggests asymmetries under which these conditions would be met, but these asymmetries appear to be too small to account for the observed baryon-antibaryon asymmetry of the universe.

Hadron epoch

[edit]- Between 10−5 second and 1 second after the Big Bang

The quark–gluon plasma that composes the universe cools until hadrons, including baryons such as protons and neutrons, can form. Initially, hadron/anti-hadron pairs could form, so matter and antimatter were in thermal equilibrium. However, as the temperature of the universe continued to fall, new hadron/anti-hadron pairs were no longer produced, and most of the newly formed hadrons and anti-hadrons annihilated each other, giving rise to pairs of high-energy photons. A comparatively small residue of hadrons remained at about 1 second of cosmic time, when this epoch ended.

Theory predicts that about 1 neutron remained for every 6 protons, with the ratio falling to 1:7 over time due to neutron decay. This is believed to be correct because, at a later stage, the neutrons and some of the protons fused, leaving hydrogen, a hydrogen isotope called deuterium, helium and other elements, which can be measured. A 1:7 ratio of hadrons would indeed produce the observed element ratios in the early and current universe.[34]

Neutrino decoupling and cosmic neutrino background (CνB)

[edit]- Around 1 second after the Big Bang

At approximately 1 second after the Big Bang neutrinos decouple and begin travelling freely through space. As neutrinos rarely interact with matter, these neutrinos still exist today, analogous to the much later cosmic microwave background emitted during recombination, around 370,000 years after the Big Bang. The neutrinos from this event have a very low energy, around 10−10 times the amount of those observable with present-day direct detection.[35] Even high-energy neutrinos are notoriously difficult to detect, so this cosmic neutrino background (CνB) may not be directly observed in detail for many years, if at all.[35]

However, Big Bang cosmology makes many predictions about the CνB, and there is very strong indirect evidence that the CνB exists, both from Big Bang nucleosynthesis predictions of the helium abundance, and from anisotropies in the cosmic microwave background (CMB). One of these predictions is that neutrinos will have left a subtle imprint on the CMB. It is well known that the CMB has irregularities. Some of the CMB fluctuations were roughly regularly spaced, because of the effect of baryonic acoustic oscillations. In theory, the decoupled neutrinos should have had a very slight effect on the phase of the various CMB fluctuations.[35]

In 2015, it was reported that such shifts had been detected in the CMB. Moreover, the fluctuations corresponded to neutrinos of almost exactly the temperature predicted by Big Bang theory (1.96 ± 0.02K compared to a prediction of 1.95K), and exactly three types of neutrino, the same number of neutrino flavors predicted by the Standard Model.[35]

Possible formation of primordial black holes

[edit]- May have occurred within about 1 second after the Big Bang

Primordial black holes are a hypothetical type of black hole proposed in 1966,[36] that may have formed during the so-called radiation-dominated era, due to the high densities and inhomogeneous conditions within the first second of cosmic time. Random fluctuations could lead to some regions becoming dense enough to undergo gravitational collapse, forming black holes. Current understandings and theories place tight limits on the abundance and mass of these objects.

Typically, primordial black hole formation requires density contrasts (regional variations in the universe's density) of around (10%), where is the average density of the universe.[37] Several mechanisms could produce dense regions meeting this criterion during the early universe, including reheating, cosmological phase transitions and (in so-called "hybrid inflation models") axion inflation. Since primordial black holes didn't form from stellar gravitational collapse, their masses can be far below stellar mass (~2×1033 g). Stephen Hawking calculated in 1971 that primordial black holes could have a mass as small as 10−5 g.[38] But they can have any size, so they could also be large, and may have contributed to the formation of galaxies.

Lepton epoch

[edit]- Between 1 second and 10 seconds after the Big Bang

The majority of hadrons and anti-hadrons annihilate each other at the end of the hadron epoch, leaving leptons (such as the electron, muons and certain neutrinos) and antileptons, dominating the mass of the universe.

The lepton epoch follows a similar path to the earlier hadron epoch. Initially leptons and antileptons are produced in pairs. About 10 seconds after the Big Bang the temperature of the universe falls to the point at which new lepton–antilepton pairs are no longer created and most remaining leptons and antileptons quickly annihilated each other, giving rise to pairs of high-energy photons, and leaving a small residue of non-annihilated leptons.[39][40][41]

Photon epoch

[edit]- Between 10 seconds and 370,000 years after the Big Bang

After most leptons and antileptons are annihilated at the end of the lepton epoch, most of the mass–energy in the universe is left in the form of photons.[41] (Much of the rest of its mass–energy is in the form of neutrinos and other relativistic particles.[citation needed]) Therefore, the energy of the universe, and its overall behavior, is dominated by its photons. These photons continue to interact frequently with charged particles, i.e., electrons, protons and (eventually) nuclei. They continue to do so for about the next 370,000 years.

Nucleosynthesis of light elements

[edit]- Between 2 minutes and 20 minutes after the Big Bang[42]

Between about 2 and 20 minutes after the Big Bang, the temperature and pressure of the universe allowed nuclear fusion to occur, giving rise to nuclei of a few light elements beyond hydrogen ("Big Bang nucleosynthesis"). About 25% of the protons, and all[34] the neutrons fuse to form deuterium, a hydrogen isotope, and most of the deuterium quickly fuses to form helium-4.

Atomic nuclei will easily unbind (break apart) above a certain temperature, related to their binding energy. From about 2 minutes, the falling temperature means that deuterium no longer unbinds, and is stable, and starting from about 3 minutes, helium and other elements formed by the fusion of deuterium also no longer unbind and are stable.[43]

The short duration and falling temperature means that only the simplest and fastest fusion processes can occur. Only tiny amounts of nuclei beyond helium are formed, because nucleosynthesis of heavier elements is difficult and requires thousands of years even in stars.[34] Small amounts of tritium (another hydrogen isotope) and beryllium-7 and -8 are formed, but these are unstable and are quickly lost again.[34] A small amount of deuterium is left unfused because of the very short duration.[34]

Therefore, the only stable nuclides created by the end of Big Bang nucleosynthesis are protium (single proton/hydrogen nucleus), deuterium, helium-3, helium-4, and lithium-7.[44] By mass, the resulting matter is about 75% hydrogen nuclei, 25% helium nuclei, and perhaps 10−10 by mass of lithium-7. The next most common stable isotopes produced are lithium-6, beryllium-9, boron-11, carbon, nitrogen and oxygen ("CNO"), but these have predicted abundances of between 5 and 30 parts in 1015 by mass, making them essentially undetectable and negligible.[45][46]

The amounts of each light element in the early universe can be estimated from old galaxies, and is strong evidence for the Big Bang.[34] For example, the Big Bang should produce about 1 neutron for every 7 protons, allowing for 25% of all nucleons to be fused into helium-4 (2 protons and 2 neutrons out of every 16 nucleons), and this is the amount we find today, and far more than can be easily explained by other processes.[34] Similarly, deuterium fuses extremely easily; any alternative explanation must also explain how conditions existed for deuterium to form, but also left some of that deuterium unfused and not immediately fused again into helium.[34] Any alternative must also explain the proportions of the various light elements and their isotopes. A few isotopes, such as lithium-7, were found to be present in amounts that differed from theory, but over time, these differences have been resolved by better observations.[34]

Matter domination

[edit]- 47,000 years after the Big Bang

Until now, the universe's large-scale dynamics and behavior have been determined mainly by radiation—meaning, those constituents that move relativistically (at or near the speed of light), such as photons and neutrinos.[47] As the universe cools, from around 47,000 years (redshift z = 3600),[3] the universe's large-scale behavior becomes dominated by matter instead. This occurs because the energy density of matter begins to exceed both the energy density of radiation and the vacuum energy density.[48] Around or shortly after 47,000 years, the densities of non-relativistic matter (atomic nuclei) and relativistic radiation (photons) become equal, the Jeans length, which determines the smallest structures that can form (due to competition between gravitational attraction and pressure effects), begins to fall and perturbations, instead of being wiped out by free streaming radiation, can begin to grow in amplitude.

According to the Lambda-CDM model, by this stage, the matter in the universe is around 84.5% cold dark matter and 15.5% "ordinary" matter. There is overwhelming evidence that dark matter exists and dominates the universe, but since the exact nature of dark matter is still not understood, the Big Bang theory does not presently cover any stages in its formation.

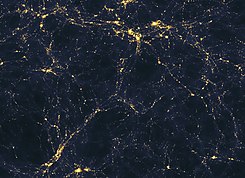

From this point on, and for several billion years to come, the presence of dark matter accelerates the formation of structure in the universe. In the early universe, dark matter gradually gathers in huge filaments under the effects of gravity, collapsing faster than ordinary (baryonic) matter because its collapse is not slowed by radiation pressure. This amplifies the tiny inhomogeneities (irregularities) in the density of the universe which was left by cosmic inflation. Over time, slightly denser regions become denser and slightly rarefied (emptier) regions become more rarefied. Ordinary matter eventually gathers together faster than it would otherwise do, because of the presence of these concentrations of dark matter.

The properties of dark matter that allow it to collapse quickly without radiation pressure, also mean that it cannot lose energy by radiation either. Losing energy is necessary for particles to collapse into dense structures beyond a certain point. Therefore, dark matter collapses into huge but diffuse filaments and haloes, and not into stars or planets. Ordinary matter, which can lose energy by radiation, forms dense objects and also gas clouds when it collapses.

Recombination, photon decoupling, and the cosmic microwave background (CMB)

[edit]

About 370,000 years after the Big Bang, two connected events occurred: the ending of recombination and photon decoupling. Recombination describes the ionized particles combining to form the first neutral atoms, and decoupling refers to the photons released ("decoupled") as the newly formed atoms settle into more stable energy states.

Just before recombination, the baryonic matter in the universe was at a temperature where it formed a hot ionized plasma. Most of the photons in the universe interacted with electrons and protons, and could not travel significant distances without interacting with ionized particles. As a result, the universe was opaque or "foggy". Although there was light, it was not possible to see, nor can we observe that light through telescopes.

Starting around 18,000 years, the universe has cooled to a point where free electrons can combine with helium nuclei to form He+

atoms. Neutral helium nuclei then start to form at around 100,000 years, with neutral hydrogen formation peaking around 260,000 years.[52] This process is known as recombination.[53] The name is slightly inaccurate and is given for historical reasons: in fact the electrons and atomic nuclei were combining for the first time.

At around 100,000 years, the universe had cooled enough for helium hydride, the first molecule, to form.[54] In April 2019, this molecule was first announced to have been observed in interstellar space, in NGC 7027, a planetary nebula within this galaxy.[54] (Much later, atomic hydrogen reacted with helium hydride to create molecular hydrogen, the fuel required for star formation.[54])

Directly combining in a low energy state (ground state) is less efficient, so these hydrogen atoms generally form with the electrons still in a high-energy state, and once combined, the electrons quickly release energy in the form of one or more photons as they transition to a low energy state. This release of photons is known as photon decoupling. Some of these decoupled photons are captured by other hydrogen atoms, the remainder remain free. By the end of recombination, most of the protons in the universe have formed neutral atoms. This change from charged to neutral particles means that the mean free path photons can travel before capture in effect becomes infinite, so any decoupled photons that have not been captured can travel freely over long distances (see Thomson scattering). The universe has become transparent to visible light, radio waves and other electromagnetic radiation for the first time in its history.

| The background of this box approximates the original 4000 K color of the photons released during decoupling, before they became redshifted to form the cosmic microwave background. The entire universe would have appeared as a brilliantly glowing fog of a color similar to this and a temperature of 4000 K, at the time. |

The photons released by these newly formed hydrogen atoms initially had a temperature/energy of around ~ 4000 K. This would have been visible to the eye as a pale yellow/orange tinted, or "soft", white color.[55] Over billions of years since decoupling, as the universe has expanded, the photons have been red-shifted from visible light to radio waves (microwave radiation corresponding to a temperature of about 2.7 K). Red shifting describes the photons acquiring longer wavelengths and lower frequencies as the universe expanded over billions of years, so that they gradually changed from visible light to radio waves. These same photons can still be detected as radio waves today. They form the cosmic microwave background, and they provide crucial evidence of the early universe and how it developed.

Around the same time as recombination, existing pressure waves within the electron-baryon plasma—known as baryon acoustic oscillations—became embedded in the distribution of matter as it condensed, giving rise to a very slight preference in distribution of large-scale objects. Therefore, the cosmic microwave background is a picture of the universe at the end of this epoch including the tiny fluctuations generated during inflation (see 9-year WMAP image), and the spread of objects such as galaxies in the universe is an indication of the scale and size of the universe as it developed over time.[56]

The Dark Ages and large-scale structure emergence

[edit]- 370 thousand to about 1 billion years after the Big Bang[57]

Dark Ages

[edit]After recombination and decoupling, the universe was transparent and had cooled enough to allow light to travel long distances, but there were no light-producing structures such as stars and galaxies. Stars and galaxies are formed when dense regions of gas form due to the action of gravity, and this takes a long time within a near-uniform density of gas and on the scale required, so it is estimated that stars did not exist for perhaps hundreds of millions of years after recombination.

This period, known as the Dark Ages, began around 370,000 years after the Big Bang. During the Dark Ages, the temperature of the universe cooled from some 4000 K to about 60 K (3727 °C to about −213 °C), and only two sources of photons existed: the photons released during recombination/decoupling (as neutral hydrogen atoms formed), which we can still detect today as the cosmic microwave background (CMB), and photons occasionally released by neutral hydrogen atoms, known as the 21 cm spin line of neutral hydrogen. The hydrogen spin line is in the microwave range of frequencies, and within 3 million years,[citation needed] the CMB photons had redshifted out of visible light to infrared; from that time until the first stars, there were no visible light photons. Other than perhaps some rare statistical anomalies, the universe was truly dark.

The first generation of stars, known as Population III stars, formed within a few hundred million years after the Big Bang.[58] These stars were the first source of visible light in the universe after recombination. Structures may have begun to emerge from around 150 million years, and early galaxies emerged from around 180 to 700 million years.[citation needed] As they emerged, the Dark Ages gradually ended. Because this process was gradual, the Dark Ages only ended fully at around 1 billion years, as the universe took on its present appearance.[citation needed]

Oldest observations of stars and galaxies

[edit]At present, the oldest observations of stars and galaxies are from shortly after the start of reionization, with galaxies such as GN-z11 (Hubble Space Telescope, 2016) at about z≈11.1 (about 400 million years cosmic time).[59][60][61][62] Hubble's successor, the James Webb Space Telescope, launched December 2021, is designed to detect objects up to 100 times fainter than Hubble, and much earlier in the history of the universe, back to redshift z≈20 (about 180 million years cosmic time).[63][64] This is believed to be earlier than the first galaxies, and around the era of the first stars.[63]

There is also an observational effort underway to detect the faint 21 cm spin line radiation, as it is in principle an even more powerful tool than the cosmic microwave background for studying the early universe.

Earliest structures and stars emerge

[edit]- Around 150 million to 1 billion years after the Big Bang

The matter in the universe is around 84.5% cold dark matter and 15.5% "ordinary" matter. Since the start of the matter-dominated era, dark matter has gradually been gathering in huge spread-out (diffuse) filaments under the effects of gravity. Ordinary matter eventually gathers together faster than it would otherwise do, because of the presence of these concentrations of dark matter. It is also slightly more dense at regular distances due to early baryon acoustic oscillations (BAO) which became embedded into the distribution of matter when photons decoupled. Unlike dark matter, ordinary matter can lose energy by many routes, which means that as it collapses, it can lose the energy which would otherwise hold it apart, and collapse more quickly, and into denser forms. Ordinary matter gathers where dark matter is denser, and in those places it collapses into clouds of mainly hydrogen gas. The first stars and galaxies form from these clouds. Where numerous galaxies have formed, galaxy clusters and superclusters will eventually arise. Large voids with few stars will develop between them, marking where dark matter became less common.

The exact timings of the first stars, galaxies, supermassive black holes, and quasars, and the start and end timings and progression of the period known as reionization, are still being actively researched, with new findings published periodically. As of 2019[update]: the earliest confirmed galaxies (for example GN-z11) date from around 380–400 million years, suggesting surprisingly fast gas cloud condensation and stellar birth rates; and observations of the Lyman-alpha forest, and of other changes to the light from ancient objects, allow the timing for reionization and its eventual end to be narrowed down. But these are all still areas of active research.

Structure formation in the Big Bang model proceeds hierarchically, due to gravitational collapse, with smaller structures forming before larger ones. The earliest structures to form are the first stars (known as Population III stars), dwarf galaxies, and quasars (which are thought to be bright, early active galaxies containing a supermassive black hole surrounded by an inward-spiralling accretion disk of gas). Before this epoch, the evolution of the universe could be understood through linear cosmological perturbation theory: that is, all structures could be understood as small deviations from a perfect homogeneous universe. This is computationally relatively easy to study. At this point non-linear structures begin to form, and the computational problem becomes much more difficult, involving, for example, N-body simulations with billions of particles. The Bolshoi cosmological simulation is a high precision simulation of this era.

These Population III stars are also responsible for turning the few light elements that were formed in the Big Bang (hydrogen, helium and small amounts of lithium) into many heavier elements. They can be huge as well as perhaps small—and non-metallic (no elements except hydrogen and helium). The larger stars have very short lifetimes compared to most Main Sequence stars we see today, so they commonly finish burning their hydrogen fuel and explode as supernovae after mere millions of years, seeding the universe with heavier elements over repeated generations. They mark the start of the Stelliferous Era.

As yet, no Population III stars have been found, so the understanding of them is based on computational models of their formation and evolution. Fortunately, observations of the cosmic microwave background radiation can be used to date when star formation began in earnest. Analysis of such observations made by the Planck microwave space telescope in 2016 concluded that the first generation of stars may have formed from around 300 million years after the Big Bang.[65]

The October 2010 discovery of UDFy-38135539, the first observed galaxy to have existed during the following reionization epoch, gives us a window into these times. Subsequently, Leiden University's Rychard J. Bouwens and Garth D. Illingworth from UC Observatories/Lick Observatory found the galaxy UDFj-39546284 to be even older, at a time some 480 million years after the Big Bang or about halfway through the Dark Ages 13.2 billion years ago. In December 2012 the first candidate galaxies dating to before reionization were discovered, when UDFy-38135539, EGSY8p7 and GN-z11 galaxies were found to be around 380–550 million years after the Big Bang, 13.4 billion years ago and at a distance of around 32 billion light-years (9.8 billion parsecs).[66][67]

Quasars provide some additional evidence of early structure formation. Their light shows evidence of elements such as carbon, magnesium, iron and oxygen. This is evidence that by the time quasars formed, a massive phase of star formation had already taken place, including sufficient generations of Population III stars to give rise to these elements.

Reionization

[edit]

As the first stars, dwarf galaxies and quasars gradually form, the intense radiation they emit reionizes much of the surrounding universe; splitting the neutral hydrogen atoms back into a plasma of free electrons and protons for the first time since recombination and decoupling.

Reionization is evidenced from observations of quasars. Quasars are a form of active galaxy, and the most luminous objects observed in the universe. Electrons in neutral hydrogen have specific patterns of absorbing ultraviolet photons, related to electron energy levels and called the Lyman series. Ionized hydrogen does not have electron energy levels of this kind. Therefore, light travelling through ionized hydrogen and neutral hydrogen shows different absorption lines. Ionized hydrogen in the intergalactic medium (particularly electrons) can scatter light through Thomson scattering as it did before recombination, but the expansion of the universe and clumping of gas into galaxies resulted in a concentration too low to make the universe fully opaque by the time of reionization. Because of the immense distance travelled by light (billions of light years) to reach Earth from structures existing during reionization, any absorption by neutral hydrogen is redshifted by various amounts, rather than by one specific amount, indicating when the absorption of then-ultraviolet light happened. These features make it possible to study the state of ionization at many different times in the past.

Reionization began as "bubbles" of ionized hydrogen which became larger over time until the entire intergalactic medium was ionized, when the absorption lines by neutral hydrogen become rare.[68] The absorption was due to the general state of the universe (the intergalactic medium) and not due to passing through galaxies or other dense areas.[68] Reionization might have started to happen as early as z = 16 (250 million years of cosmic time) and was mostly complete by around z = 9 or 10 (500 million years), with the remaining neutral hydrogen becoming fully ionized z = 5 or 6 (1 billion years), when Gunn-Peterson troughs that show the presence of large amounts of neutral hydrogen disappear. The intergalactic medium remains predominantly ionized to the present day, the exception being some remaining neutral hydrogen clouds, which cause Lyman-alpha forests to appear in spectra.

These observations have narrowed down the period of time during which reionization took place, but the source of the photons that caused reionization is still not completely certain. To ionize neutral hydrogen, an energy larger than 13.6 eV is required, which corresponds to ultraviolet photons with a wavelength of 91.2 nm or shorter, implying that the sources must have produced significant amount of ultraviolet and higher energy. Protons and electrons will recombine if energy is not continuously provided to keep them apart, which also sets limits on how numerous the sources were and their longevity.[69] With these constraints, it is expected that quasars and first generation stars and galaxies were the main sources of energy.[70] The current leading candidates from most to least significant are currently believed to be Population III stars (the earliest stars; possibly 70%),[71][72] dwarf galaxies (very early small high-energy galaxies; possibly 30%),[73] and a contribution from quasars (a class of active galactic nuclei).[69][74][75]

However, by this time, matter had become far more spread out due to the ongoing expansion of the universe. Although the neutral hydrogen atoms were again ionized, the plasma was much more thin and diffuse, and photons were much less likely to be scattered. Despite being reionized, the universe remained largely transparent during reionization due how sparse the intergalactic medium was. Reionization gradually ended as the intergalactic medium became virtually completely ionized, although some regions of neutral hydrogen do exist, creating Lyman-alpha forests.

In August 2023, images of black holes and related matter in the very early universe by the James Webb Space Telescope were reported and discussed.[76]

Galaxies, clusters and superclusters

[edit]

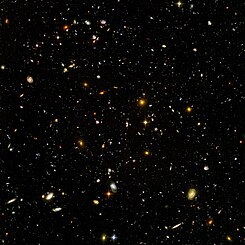

Matter continues to draw together under the influence of gravity, to form galaxies. The stars from this time period, known as Population II stars, are formed early on in this process, with more recent Population I stars formed later. Gravitational attraction also gradually pulls galaxies towards each other to form groups, clusters and superclusters. Hubble Ultra Deep Field observations has identified a number of small galaxies merging to form larger ones, at 800 million years of cosmic time (13 billion years ago).[78] (This age estimate is now believed to be slightly overstated).[79]

Using the 10-metre Keck II telescope on Mauna Kea, Richard Ellis of the California Institute of Technology at Pasadena and his team found six star forming galaxies about 13.2 billion light-years away and therefore created when the universe was only 500 million years old.[80] Only about 10 of these extremely early objects are currently known.[81] More recent observations have shown these ages to be shorter than previously indicated. The most distant galaxy observed as of October 2016[update], GN-z11, has been reported to be 32 billion light-years away,[66][82] a vast distance made possible through spacetime expansion (z = 11.1;[66] comoving distance of 32 billion light-years;[82] lookback time of 13.4 billion years[82]).

Present and future

[edit]The universe has appeared much the same as it does now, for many billions of years. It will continue to look similar for many more billions of years into the future. The galactic disk of the Milky Way is estimated to have been formed 8.8 ± 1.7 billion years ago but only the age of the Sun, 4.567 billion years, is known precisely.[83]

Dark energy–dominated era

[edit]- From about 9.8 billion years after the Big Bang

From about 9.8 billion years of cosmic time,[13] the universe's large-scale behavior is believed to have gradually changed for the third time in its history. Its behavior had originally been dominated by radiation (relativistic constituents such as photons and neutrinos) for the first 47,000 years, and since about 370,000 years of cosmic time, its behavior had been dominated by matter. During its matter-dominated era, the expansion of the universe had begun to slow down, as gravity reined in the initial outward expansion. But from about 9.8 billion years of cosmic time, observations show that the expansion of the universe slowly stops decelerating, and gradually begins to accelerate again, instead.

While the precise cause is not known, the observation is accepted as correct by the cosmologist community. By far the most accepted understanding is that this is due to an unknown form of energy which has been given the name "dark energy".[84][85] "Dark" in this context means that it is not directly observed, but its existence can be deduced by examining the gravitational effect it has on the universe. Research is ongoing to understand this dark energy. Dark energy is now believed to be the single largest component of the universe, as it constitutes about 68.3% of the entire mass–energy of the physical universe.

Dark energy is believed to act like a cosmological constant—a scalar field that exists throughout space. Unlike gravity, the effects of such a field do not diminish (or only diminish slowly) as the universe grows. While matter and gravity have a greater effect initially, their effect quickly diminishes as the universe continues to expand. Objects in the universe, which are initially seen to be moving apart as the universe expands, continue to move apart, but their outward motion gradually slows down. This slowing effect becomes smaller as the universe becomes more spread out. Eventually, the outward and repulsive effect of dark energy begins to dominate over the inward pull of gravity. Instead of slowing down and perhaps beginning to move inward under the influence of gravity, from about 9.8 billion years of cosmic time, the expansion of space starts to slowly accelerate outward at a gradually increasing rate.

The far future and ultimate fate

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2021) |

There are several competing scenarios for the long-term evolution of the universe. Which of them will happen, if any, depends on the precise values of physical constants such as the cosmological constant, the possibility of proton decay, the energy of the vacuum (meaning, the energy of "empty" space itself), and the natural laws beyond the Standard Model.

If the expansion of the universe continues and it stays in its present form, eventually all but the nearest galaxies will be carried away from us by the expansion of space at such a velocity that the observable universe will be limited to our own gravitationally bound local galaxy cluster. In the very long term (after many trillions—thousands of billions—of years, cosmic time), the Stelliferous Era will end, as stars cease to be born and even the longest-lived stars gradually die. Beyond this, all objects in the universe will cool and (with the possible exception of protons) gradually decompose back to their constituent particles and then into subatomic particles and very low-level photons and other fundamental particles, by a variety of possible processes.

Ultimately, in the extreme future, the following scenarios have been proposed for the ultimate fate of the universe:

| Scenario | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Heat Death | As expansion continues, the universe becomes larger, colder, and more dilute; in time, all structures eventually decompose to subatomic particles and photons. | In the case of indefinitely continuing cosmic expansion, the energy density in the universe will decrease until, after an estimated time of 101000 years, it reaches thermodynamic equilibrium and no more structure will be possible. This will happen only after an extremely long time because first, some (less than 0.1%)[87] matter will collapse into black holes, which will then evaporate extremely slowly via Hawking radiation. The universe in this scenario will cease to be able to support life much earlier than this, after some 1014 years or so, when star formation ceases.[16], §IID In some Grand Unified Theories, proton decay after at least 1034 years will convert the remaining interstellar gas and stellar remnants into leptons (such as positrons and electrons) and photons. Some positrons and electrons will then recombine into photons.[16], §IV, §VF In this case, the universe has reached a high-entropy state consisting of a bath of particles and low-energy radiation. It is not known however whether it eventually achieves thermodynamic equilibrium.[16], §VIB, VID The hypothesis of a universal heat death stems from the 1850s ideas of William Thomson (Lord Kelvin), who extrapolated the classical theory of heat and irreversibility (as embodied in the first two laws of thermodynamics) to the universe as a whole.[88] |

| Big Rip | Expansion of space accelerates and at some point becomes so extreme that even subatomic particles and the fabric of spacetime are pulled apart and unable to exist. | For any value of the dark energy content of the universe where the negative pressure ratio is less than −1, the expansion rate of the universe will continue to increase without limit. Gravitationally bound systems, such as clusters of galaxies, galaxies, and ultimately the Solar System will be torn apart. Eventually the expansion will be so rapid as to overcome the electromagnetic forces holding molecules and atoms together. Even atomic nuclei will be torn apart. Finally, forces and interactions even on the Planck scale—the smallest size for which the notion of "space" currently has a meaning—will no longer be able to occur as the fabric of spacetime itself is pulled apart and the universe as we know it will end in an unusual kind of singularity. |

| Big Crunch | Expansion eventually slows and halts, then reverses as all matter accelerates towards its common centre. Currently considered to be likely incorrect. | In the opposite of the "Big Rip" scenario, the expansion of the universe would at some point be reversed and the universe would contract towards a hot, dense state. This is a required element of oscillatory universe scenarios, such as the cyclic model, although a Big Crunch does not necessarily imply an oscillatory universe. Current observations suggest that this model of the universe is unlikely to be correct, and the expansion will continue or even accelerate. |

| Vacuum instability | Collapse of the quantum fields that underpin all forces, particles and structures, to a different form. | Cosmology traditionally has assumed a stable or at least metastable universe, but the possibility of a false vacuum in quantum field theory implies that the universe at any point in spacetime might spontaneously collapse into a lower-energy state (see Bubble nucleation), a more stable or "true vacuum", which would then expand outward from that point with the speed of light.[89][90][91][92][93]

The effect would be that the quantum fields that underpin all forces, particles and structures, would undergo a transition to a more stable form. New forces and particles would replace the present ones we know of, with the side effect that all current particles, forces and structures would be destroyed and subsequently (if able) reform into different particles, forces and structures. |

In this kind of extreme timescale, extremely rare quantum phenomena may also occur that are extremely unlikely to be seen on a timescale smaller than trillions of years. These may also lead to unpredictable changes to the state of the universe which would not be likely to be significant on any smaller timescale. For example, on a timescale of millions of trillions of years, black holes might appear to evaporate almost instantly, uncommon quantum tunnelling phenomena would appear to be common, and quantum (or other) phenomena so unlikely that they might occur just once in a trillion years may occur many times.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Age of the universe – Time elapsed since the Big Bang

- Cosmic Calendar – Method to visualize the chronology of the universe (age of the universe scaled to a single year)

- Cyclic model – Cosmological models involving indefinite, self-sustaining cycles

- Dark-energy-dominated era – Expansion of the universe parameter

- Dyson's eternal intelligence – Hypothetical concept in astrophysics

- Entropy (arrow of time) – Use of the second law of thermodynamics to distinguish past from future

- Graphical timeline from Big Bang to Heat Death – Visual representation of the universe's past, present, and future

- Graphical timeline of the Big Bang – Logarithmic chronology of the event that began the Universe

- Graphical timeline of the Stelliferous Era

- Illustris project – Computer-simulated universes

- Matter-dominated era – Expansion of the universe parameter

- Radiation-dominated era – Expansion of the universe parameter

- Timeline of the early universe

- Timeline of the far future – Scientific projections regarding the far future

- Ultimate fate of the universe – Theories about the end of the universe

Notes

[edit]- ^ 12 gauge bosons, 2 Higgs-sector scalars, 3 left-handed quarks x 2 SU(2) states x 3 SU(3) states, and 3 left-handed leptons x 2 SU(2) states, 6 right-handed quarks x 3 SU(3) states and 6 right-handed leptons, all but the scalar having 2 spin states

References

[edit]- ^ Planck Collaboration (October 2016). "Planck 2015 results. XIII. Cosmological parameters". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 594: Article A13. arXiv:1502.01589. Bibcode:2016A&A...594A..13P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201525830. S2CID 119262962. The Planck Collaboration in 2015 published the estimate of 13.799 ± 0.021 billion years ago (68% confidence interval). See PDF: page 32, Table 4, Age/Gyr, last column.

- ^ Schombert, James. "Birth of the Universe". HC 441: Cosmology. University of Oregon. Archived from the original on 28 November 2018. Retrieved March 20, 2022.

- ^ a b c Ryden 2006, eq. 6.41

- ^ Tanabashi, M. 2018, p. 358, chpt. 21.4.1: "Big-Bang Cosmology" (Revised September 2017) by Keith A. Olive and John A. Peacock.

- ^ Notes: Edward L. Wright's Javascript Cosmology Calculator (last modified 23 July 2018). With a default = 69.6 (based on WMAP9+SPT+ACT+6dFGS+BOSS/DR11+H0/Riess) parameters, the calculated age of the universe with a redshift of z = 1100 is in agreement with Olive and Peacock (about 370,000 years).

- ^ Hinshaw et al. 2009. See PDF: p. 242, Table 7, Age at decoupling, last column. Based on WMAP+BAO+SN parameters, the age of decoupling occurred 376971+3162

−3167 years after the Big Bang. - ^ Ryden 2006, pp. 194–195. "Without going into the details of the non-equilibrium physics, let's content ourselves by saying, in round numbers, zdec ≈ 1100, corresponding to a temperature Tdec ≈ 3000 K, when the age of the universe was tdec ≈ 350,000 yr in the Benchmark Model. (...) The relevant times of various events around the time of recombination are shown in Table 9.1. (...) Note that all these times are approximate, and are dependent on the cosmological model you choose. (I have chosen the Benchmark Model in calculating these numbers.)"

- ^ a b S.V. Pilipenko (2013–2021) "Paper-and-pencil cosmological calculator" arxiv:1303.5961, including Fortran-90 code upon which the citing charts and formulae are based.

- ^ Chen, Ke-Jung; Heger, Alexander; Woosley, Stan; et al. (1 September 2014). "Pair Instability Supernovae of Very Massive Population III Stars". The Astrophysical Journal. 792 (1): Article 44. arXiv:1402.5960. Bibcode:2014ApJ...792...44C. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/792/1/44. S2CID 119296923.

- ^ Cesari, Thaddeus (9 December 2022). "NASA's Webb Reaches New Milestone in Quest for Distant Galaxies". Retrieved 14 November 2023.

- ^ Curtis-Lake, Emma; et al. (December 2022). "Spectroscopy of four metal-poor galaxies beyond redshift ten" (PDF). Nature. arXiv:2212.04568.

- ^ del Peloso, Eduardo F.; da Silva, Licio; Porto de Mello, Gustavo F.; et al. (5 September 2005). "The age of the Galactic thin disk from Th/Eu nucleocosmochronology – III. Extended sample" (PDF). Stellar atmospheres. Astronomy & Astrophysics. 440 (3): 1153–1159. arXiv:astro-ph/0506458. Bibcode:2005A&A...440.1153D. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20053307. S2CID 16484977. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 May 2019.

- ^ a b c Ryden 2006, eq. 6.33

- ^ Bruce, Dorminey (1 February 2021). "The Beginning to the End of the Universe: The mystery of dark energy". Astronomy.com. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ Gibbons, Hawking & Siklos 1983, pp. 171–204, "Phase transitions in the very early Universe" by Alan H. Guth..

- ^ a b c d e Adams, Fred C.; Laughlin, Gregory (1 April 1997). "A dying universe: The long-term fate and evolution of astrophysical objects". Reviews of Modern Physics. 69 (2): 337–372. arXiv:astro-ph/9701131. Bibcode:1997RvMP...69..337A. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.69.337. S2CID 12173790.

- ^ "The Planck Epoch". The Universe Adventure. Berkeley, CA: Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. 7 August 2007. Archived from the original on 5 July 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- ^ a b Ryden 2003, p. 196

- ^ Lidsey, James E. (1997). "Reconstructing the inflaton potential—an overview". Reviews of Modern Physics. 69 (2): 373–410. arXiv:astro-ph/9508078. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.69.373.

- ^ "BICEP2 March 2014 Results and Data Products". The BICEP and Keck Array CMB Experiments. Cambridge, MA: FAS Research Computing, Harvard University. 16 December 2014 [Results originally released on 17 March 2014]. Archived from the original on 18 March 2014. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- ^ Clavin, Whitney (17 March 2014). "NASA Technology Views Birth of the Universe". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Washington, D.C.: NASA. Archived from the original on 10 October 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (17 March 2014). "Space Ripples Reveal Big Bang's Smoking Gun". Space & Cosmos. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 17 March 2014. Retrieved 6 January 2020. "A version of this article appears in print on March 18, 2014, Section A, Page 1 of the New York edition with the headline: Space Ripples Reveal Big Bang’s Smoking Gun." The online version of this article was originally titled "Detection of Waves in Space Buttresses Landmark Theory of Big Bang".

- ^ a b Ade, Peter A.R.; et al. (BICEP2 Collaboration) (20 June 2014). "Detection of B-Mode Polarization at Degree Angular Scales by BICEP2". Physical Review Letters. 112 (24): 241101. arXiv:1403.3985. Bibcode:2014PhRvL.112x1101B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.112.241101. PMID 24996078. S2CID 22780831.

- ^ Woit, Peter (13 May 2014). "BICEP2 News". Not Even Wrong (Blog). New York: Department of Mathematics, Columbia University. Archived from the original on 8 October 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (19 June 2014). "Astronomers Hedge on Big Bang Detection Claim". Space & Cosmos. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 14 July 2019. Retrieved June 20, 2014. "A version of this article appears in print on June 20, 2014, Section A, Page 16 of the New York edition with the headline: Astronomers Stand by Their Big Bang Finding, but Leave Room for Debate."

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (19 June 2014). "Cosmic inflation: Confidence lowered for Big Bang signal". Science & Environment. BBC News. Archived from the original on 20 June 2014. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

- ^ Ade, Peter A.R.; et al. (BICEP2/Keck, Planck Collaborations) (13 March 2015). "Joint Analysis of BICEP2/Keck Array and Planck Data". Physical Review Letters. 114 (10): 101301. arXiv:1502.00612. Bibcode:2015PhRvL.114j1301B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.114.101301. PMID 25815919. S2CID 218078264.

- ^ Clavin, Whitney (30 January 2015). "Gravitational Waves from Early Universe Remain Elusive". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Washington, D.C.: NASA. Archived from the original on 3 May 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (30 January 2015). "Speck of Interstellar Dust Obscures Glimpse of Big Bang". Science. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 16 July 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2015. "A version of this article appears in print on Jan. 31, 2015, Section A, Page 11 of the New York edition with the headline: Speck of Interstellar Dust Obscures Glimpse of Big Bang."